Buzzard vs vulture: What’s the Difference Between Buzzards and Vultures?

What’s the Difference Between Buzzards and Vultures?

Buzzards vs vultures—you may think they are the same birds. Though buzzards and vultures may seem like common, familiar birds, these two terms can actually be very confusing and are often mistaken for completely different species. To make matters more complicated, various types of buzzards and vultures are not always in the same family. So, what’s the difference between buzzards and vultures, and how can birders avoid these errors?

Identifying Buzzards vs. Vultures: Key Differences

There are key differences that can help you tell a buzzard apart from a vulture. Vultures are large, bald birds that sniff out carrion (decaying flesh of dead animals) and then feast on the carcasses. Buzzards are smaller than vultures and they prefer to hunt, attack, and eat their prey while the creatures are somewhat alive, though they will also eat dead animals.

What Is a Vulture?

Vultures are universally understood to be the bald, long-necked scavenging birds that get a bad reputation for their enjoyment of eating carrion. These birds actually provide a valuable ecological service, however, as they clean up carcasses and help prevent the spread of diseases to other wildlife, including humans. There are 23 vulture species in the world, in two distinct groups. The seven vulture species of the New World belong to the Cathartidae bird family, while the 16 vulture species of the Old World are in the family Accipitridae. Although these species are only distantly related, they do share many familiar characteristics and both groups are easily recognized as vultures.

What Is a Buzzard?

There are 26 bird species in the world named buzzard, including the European honey-buzzard, lizard buzzard, forest buzzard, and long-legged buzzard. At least one buzzard species can be found on every continent except Antarctica.

Buzzards are a type of hawk, specifically, buteos, and they are in the family Accipitridae. These are medium- to large-sized hawks with broad wings ideal for soaring on thermal currents.

While these birds are called buzzards in Europe, Africa, Asia, Indonesia, and Australia, the same types of birds, open-country buteos, are called hawks in much of North and South America. The familiar red-tailed hawk, for example, would likely be called a red-tailed buzzard if it were found in Europe. Even in field guides, the rough-legged buzzard (Buteo lagopus) is called the rough-legged hawk in its North American range.

Vultures Can Be Called Buzzards

Where vultures and buzzards get complicated is when the casual names of these birds overlap. While buzzards and vultures are distinctly named and separated in Europe, Africa, and Asia, some birds go by both names in North America. When European settlers first colonized New England and other parts of North America, they gave familiar names to unfamiliar birds to remind themselves of home.

Early colonists called the large, soaring birds they noticed in North American skies “buzzards” because they looked similar to the flight patterns of the buzzards in Europe. The birds those colonists were really seeing, however, were not buteo hawks but were turkey vultures and black vultures, which are widespread in eastern North America. The name stuck, and even today the North American vultures may still be commonly called buzzards, turkey buzzards, or black buzzards.

Turkey Vulture

Russ / Flickr / CC by 2.0

Regional Differences

Unraveling the types of buzzards and vultures can be baffling. Ultimately, whether a bird is a buzzard or a vulture depends on who you ask, and where you ask them. In North America, a vulture is a vulture, a buzzard is a vulture, and a hawk is a hawk. In the rest of the world, a vulture is a vulture, a buzzard is a hawk, and a hawk is sometimes a buzzard, though there are still other birds with the name hawk that would not be called buzzards.

- Turkey vulture (widely recognized common name)

- Turkey buzzard (regional common name or European variation for traveling birders)

- TUVU (four-character bird shorthand code)

- TV (more casual name code)

- Vulture or buzzard (single reference when no similar species occur regionally)

- Cathartes aura (scientific name, universally recognized worldwide)

This name confusion is why it is important for birders to learn the scientific names of birds, especially when they are birding in different parts of the world. Using scientific names ensures there is no confusion about which bird is which, particularly for research, listing, or reporting sightings. Ornithologists and wildlife officials, in particular, will use scientific names in their reports to be sure it is absolutely clear and unmistakable which birds they are referring to.

Understanding the differences between buzzards and vultures, including how different words may refer to the same birds, can help birders better communicate which birds they see and share their sightings with others.

Tip

Vultures and buzzards are scavengers, but they are not dangerous to humans and usually are not interested in attacking small pets, either. However if they feel threatened by a human or another animal, they may bite or vomit in response.

Buzzard

Henk Bogaard / Getty Images

Vulture

AndreAnita / Getty Images

Can You Name All the Vulture Species?

Vulture vs Buzzard: What’s the Difference?

Written by August Buck

Published: February 23, 2022

Aitor Lamadrid Lopez/Shutterstock.com

More Great Content:

Did you know that there is a difference between a vulture vs buzzard? While these names are often used interchangeably to describe the same bird, vultures and buzzards are actually different from one another.

In this article, we will address the various differences between vultures and buzzards, including their physical appearances so that you can learn how to tell them apart. Let’s get started and talk about these majestic birds of prey now.

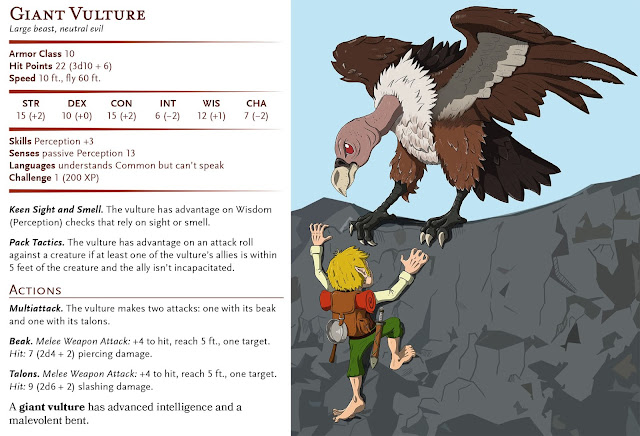

Comparing Vulture vs Buzzard

In the United States, the population refers to vultures and buzzards indistinguishably, even though these birds are different species.

A-Z-Animals.com

| Vulture | Buzzard | |

|---|---|---|

| Classification | Cathartidae or Accipitridae | Buteos |

| Diet | Dead animals and carrion | Small rodents and sometimes carrion |

| Habitat | Avoids cold habitats | Thrives just about anywhere |

| Appearance | No feathers on their heads, small feet, eyebrows; usually larger than buzzard varieties | Broad wings, rounded tails, feathers everywhere, taloned feet; usually smaller than vultures |

| Common Names | Vulture, buzzard, turkey vulture | Hawk |

Key Differences Between Vulture vs Buzzard

There are nearly 40 different species of vultures around the world, while there are only 20 or 25 species of buzzards.

Ishor gurung/Shutterstock.com

There are many key differences between vultures vs buzzards, though it depends on where you live. In the United States, the population refers to vultures and buzzards indistinguishably, even though these birds are different species. Regardless of their regional name differences, these birds have different diets and physical traits. Let’s take a look at some of these in more detail now.

Vulture vs Buzzard: Species Classification

Vultures are known for eating carrion, or dead animals, while buzzards prefer to consume live animals.

Wang LiQiang/Shutterstock.com

A key difference between vulture vs buzzard lies in their species classification. This is because vultures and buzzards are interchangeable names in a lot of locations, but they are actually different animals. Let’s talk more about their classification and name differences now.

There are nearly 40 different species of vultures around the world, while there are only 20 or 25 species of buzzards.

While this distinction will not help you identify them in the wild, it is important to note that they are indeed different birds. Their differences become more clear once you understand their appearances, diets, as well as their preferred habitats.

Vulture vs Buzzard: Diet

While vultures are capable of sniffing out dead prey from miles away, buzzards use their keen eyesight in order to find their meals.

FotoRequest/Shutterstock.com

Another key difference between vultures and buzzards is their diet preferences. Vultures are known for eating carrion, or dead animals, while buzzards prefer to consume live animals. However, even buzzards will consume dead animals or carrion when there are no other options, but they do prefer to eat live rodents such as rabbits or rats.

Vultures have a notorious reputation for eating dead animals as they circle overhead in the sky. While vultures are capable of sniffing out dead prey from miles away, buzzards use their keen eyesight in order to find their meals. This is not only a key difference in their dietary preferences, but also their physical capabilities.

Vulture vs Buzzard: Appearance

Buzzards look more like a traditional bird of prey compared to vultures, covered in feathers and complete with powerful talents and keen eyes.

iStock.com/MriyaWildlife

Vultures vs buzzards look different in their overall physical appearance. This is very obvious when you put these two birds side by side, as vultures are notorious for having bald heads, free of feathers. Buzzards look more like a traditional bird of prey, covered in feathers and complete with powerful talents and keen eyes.

Depending on the species, the majority of vultures are larger than buzzards. Their wingspan is impressive, and they have a different flight pattern when compared to buzzards.

The necks of vultures are also much longer than the necks of buzzards. Their bodies are large and slow in comparison to buzzards as well, given that buzzards need a bit more mobility in order to hunt and fly.

Vulture vs Buzzard: Habitat Preferences

The necks of vultures are much longer than the necks of buzzards.

Sourabh Bharti/Shutterstock.com

A final difference between a vulture vs buzzard lies in their preferred habitat. Vultures prefer to avoid cold climates, while buzzards are found all over the world in a wide variety of habitats. But why might this be? Let’s go over some of these reasons in more detail now.

Buzzards enjoy many different climates and biomes, including open meadows and plains where they can easily hunt for their prey.

Given the bald headedness of vultures, they are incapable of regulating their temperatures in cold climates. Vultures thrive in warm areas with reasonable winters, while buzzards remain largely unaffected by cold climates. Buzzards are found throughout the world, and studies have shown that at least one buzzard species exists everywhere except Antarctica. Just like vultures, even buzzards can’t handle cold weather like that!

Share this post on:

About the Author

August Buck

I am a non-binary freelance writer working full-time in Oregon. Graduating Southern Oregon University with a BFA in Theatre and a specialization in creative writing, I have an invested interest in a variety of topics, particularly Pacific Northwest history.

How To Tell a Vulture from A Buzzard? 8 Big Differences!

What’s This Post About?

For many years, Vultures and Buzzards, popular birds of prey, have been a source of confusion for many people. However, we know that these two birds, despite numerous similarities, are not the same. In fact, there are prominently profound differences that distinguish vultures and buzzards.

To decipher between the two familiar birds, vultures, and buzzards, it is fundamental to understand the critical differences between them. The significant distinction between the two is that vultures are scavengers while buzzards are predators, making it a lot simpler to understand their physical characteristics and nature.

Vultures are relatively large birds with bald heads and necks, essentially known for their repulsive habits of eating carrions and feeding on dead creatures.

Understanding the Terms – Buzzards and Vultures

The term Buzzard is an old European word, which has been formerly used to describe species of hawks. In the US, however, Buzzard refers to the Turkey Vulture, while in many other parts of the world, including Europe, Africa, and Asia, Buzzard is the Old World Vulture, belonging to the Buteo genus, or the family of hawks.

The roots of the problem arose when the European colonists colonized New England and North America. When these novice settlers first saw the large raptor species soaring serenely in the sky, adopting similar flight patterns, they associated this resemblance to a similar bird of prey back in Europe.

Referred to as the buzzards in Europe, the dark plumaged, broad-winged birds acquired another name in America. In reality, the birds being observed were not Buteo hawks but Black Vultures and Turkey Vultures.

Mistaking them as the hawks that were prevalent back in Europe, it was too late as the Vultures had already become renowned as Buzzards in America, still creating confusion centuries later.

DID YOU KNOW?

In the US, vulture refers to the Turkey Vulture and Black Vulture.

Buzzards and Vultures are precisely named across most parts of the world, with the overlap arising in North America.

What are Vultures?

Vultures are pretty large birds of prey, widely known for their scavenging capabilities. Primarily feeding on the carcasses of dead animals and enjoying delectable treats of roadkill, they are one of the largest species of birds. Despite being repugnant for their nauseous eating habits, vultures are an incredible cleansing unit for our environment.

DID YOU KNOW?

The Hooded Vulture is the smallest species of Vultures but still has an enormous wingspan of 5 feet.

Over the years, vultures have evolved, with the modern classifications dividing them into the New World Vultures and the Old World Vultures.

A conspicuous feature of the vultures is their featherless heads – and sometimes necks as well. Their ranges can be found across all the continents except for Australia and Antarctica.

What is a Buzzard?

Buzzards are large birds of prey, dwelling in a broad range of habitats, with the common Buzzard being native to Europe and Asia. Highly adaptable species, they can survive in a wide variety of regions, from grasslands to forests and deserts.

With their rounded tail and broad wings, from afar, buzzards greatly resemble hawks. The name of the buzzards derives from the genus name Buteos. These birds usually do not form flocks unless they are migrating to a different region.

Often seen soaring in the sky in circles, the overall shape of their wings helps them fly swiftly on the air currents. These voracious predators kill and then feed on animals, preferring alive creatures over carrions.

FUN FACT

Male buzzards are considered ideal hunters due to their weight.

Similarities Between Buzzards and Vultures

Buzzards and Vultures – these two terms have greatly befuddled the minds of people. Often used interchangeably, we tend to miss out on some of the prominent distinctions between the species due to their astounding similarities.

- Both are Birds of Prey

- Both have long and broad wings that aid in soaring fluently on the thermal currents.

- Both adopt a circular motion in flight

Differences Between Vultures And Buzzards

Due to the similarities between the birds, and more so, the overlap in the colloquial terms to refer to these birds, there has been considerable confusion. Explore these differences to clear out the misconceptions regarding the two species.

1. Dietary Habits

Vultures are primarily known for their repulsive dietary habits, majorly feeding on the carcasses of dead animals, scavenging the ground for carrions, thereby eliminating the bacteria and infections.

Despite their abhorrent diet, vultures have an essential role to play in our ecosystem. After all, by ingesting the carcasses of dead creatures around, they cleanse the environment, mitigating the risk of infectious diseases.

FUN FACT

Gyphohierax angolensis – a species of vultures – is an exception. It prefers a variable diet from the other vultures, feeding on oil palm fruits.

Unlike the vultures, which rarely attack healthy animals, buzzards actively hunt and attack alive animals such as rabbits and other smaller mammals. However, they do not mind feeding on the carcasses of dead animals occasionally when other food sources are scarce.

Vultures are cautious eaters, carefully observing their surroundings for any threats before approaching their potential meal. However, the predatory nature of buzzards makes them fierce, as they fiercely attack the prey and dig into the food – not too wary of their surroundings.

2. Size

Extremely large in size, measuring about 3.

Making the vultures quite sluggish, their hefty size impacts their speed. However, the long and broad wings of the bird play a significant role in helping the bird to glide at high altitudes, only rarely flapping its wings.

The relatively small-sized, measuring around 20 inches in length and varying around 1-2 kgs in weight, Buzzards can maintain a rapid speed in flight. The predatory nature of the bird gives it greater agility, enabling it to fly at an average speed of 28mph.

The medium-sized bodies of the bird, with long broad wings extending to a wingspan of around 43-55 inches, and rounded tails greatly aid the bird to soar on the thermal currents for long hours swiftly.

3. Physical Appearance

An eminent physical trait of the Vultures is their bald head and neck. Covered in reddish skin, Vultures have a proportionately smaller head relative to their body.

Devoid of any feathers on their long neck and head, the bald feature gives the birds an irksome appearance.

Despite this, it plays an essential role in preventing any bacteria from adhering to the feathers due to the unhealthy food that they consume. In addition, the heat from the sun kills any bacteria and germs that stick to the skin while feeding, ensuring that the bird remains clean.

However, the entire body of buzzards, including their head and neck, is well covered with feathers, prominently distinguishing them from vultures.

4. Anatomical Features – Beaks and Talons

Vultures have relatively weak talons and a bluntly hooked bill. They do not need solid feet as they do not have to capture prey fiercely. Most of their prey is already dead, so they just need to rip them apart to feed on them. The relatively blunt beak is sufficient for this.

Buzzards, on the other hand, consume their prey alive. This entails it necessary for them to have a stout bill and powerful talons to capture their prey.

5. Keen Sense of Smell and Sight

Relative to the buzzards, vultures have an incredibly keen sense of smell. Soaring at high altitudes in the sky, the ability to sense vile odor from far away allows the bird to locate food. However, it primarily depends on its unusual smell to sniff carcasses from miles away.

Buzzards possess an incredibly sharp sense of sight. Relying on their whacking visual acuity, these birds of prey soar at high altitudes to search and locate potential prey, to capture and attack them actively. They would also hide amidst the dense trees to lurk their target species.

Feeding primarily on carrions, vultures are often considered obnoxious for their feeding habits. Entirely commonly found in flocks, these birds are known to surround a sick or injured creature, perhaps in anticipation, waiting for it to die, to feed on the carcasses once the animal passes away.

Buzzards often tend to be found alone, as opposed to flocks. This is because they are not very gregarious species, usually circling the sky alone. However, they form large flocks when migrating.

7. Difference in Habitat

Buzzards are not very specific about the environment they can reside in. Highly adaptable species, they can survive in a wide range of habitats, from the tropical deserts, forests, and coastal to the frigid regions and mountains; the raptor can thrive in nearly all environments.

Vultures, on the contrary, require an optimal atmosphere to thrive in. They can hardly survive in the colder regions – perhaps due to the bare skin on their body – which makes survival arduous in extreme colds. For this reason, vultures are absent in Antarctica, usually prospering in warmer regions of Europe, parts of Asia, and Africa.

8. Classification

Widely known as scavenging birds, vultures can be found across all continents except for Antarctica.

16 species are part of the Old World Vultures, belonging to the Accipitridae family, typically found in Asia, Europe, and Africa, while the New World Vultures comprises of the remaining 7 species, which are members of the Cathartidae family, dwelling in the temperate regions of America.

Belonging to the family Accipitridae and the genus of Buteo, Buzzards have 26 species. Among the many species, some types of Buzzards include the Common Buzzard, European Honey Buzzard, Long-legged Buzzard, Forest Buzzard, and Lizard Buzzard.

Keep Reading!

Though often used interchangeably, Vultures and Buzzards are two very distinct species. While vultures are scavengers, buzzards are predators. Not only do their dietary habits vary considerably, but both birds of prey have prominent variations in their physical traits that clearly set them apart.

The issue might still persist due to the different names the birds have acquired. For example, Buzzards, in some countries, is known as Vultures, whereas in others, they are referred to as Hawks. This would make it challenging to create a clear line of distinction between the two.

It is, undoubtedly, essential for birders to recognize the critical distinctions between the Vultures and Buzzards and know what the bird is called in the part of the world they are viewing it to record their observations rightly.

Do you often tend to wonder why the Vultures are often seen flying around in Circles? Read our post to find out!

Why Do Vultures Circle in The Sky? Safety First!

From afar, vultures seem to enjoy a serene flight in the sky and what’s intriguing is their circular motion. The question is, why do they do it?

By

David A. Swanson

Bird Watching USA

My name is David and I’m the the founder of Bird Watching USA! I started Bird Watching with My father-in-law many years ago, and I’ve become an addict to watching these beautiful creatures.

Posted in:

Buzzard Vs Vulture: Differences Between Scavengers Explained For Kids!

Buzzards and vultures are two ferocious birds of prey from the class of Aves.

A soaring turkey vulture in the sky above could be easily mistaken for a red-tailed hawk, with similarities in their features being noticeable during flight. However, turkey vultures are known to have longer and more rectangular wings, which they hold above themselves like the letter V.

Hawks might be less stable and steady while flying, but a turkey vulture soars high in a steady motion. In North America and South America, a buzzard is sometimes considered to be closely related to (and thus confused with) a vulture, and a hawk is often confused with a buzzard. The differences are pretty subtle. So, when someone in the US refers to a buzzard, know that they may mean a turkey vulture and not a true buzzard.

The turkey vulture is a part of the new world vultures family, while a buzzard belongs to the old world vultures and birds of prey (the Accipitridae family), of the Buteo genus. However, in North America, people mix misidentify hawks and buzzard hawks with the Buteo genus.

After reading this comparison between new world vultures and old world vultures, do check out other fun articles like turkey vulture facts and cicada vs locust.

Why are turkey vultures called buzzards?

During early colonial times, the colonists got confused and called large birds soaring high in North America buzzards. Those turkey vultures had similarities to the buzzards flying through European skies.

A slang term commonly used in the US for vultures today is ‘buzzard’. However, in the UK, Atlantic, and elsewhere in Europe, buzzard is used as a hawk name, not for vultures.

The European scavengers of 26 hawk species have buzzard in their name. Examples of the hawk species are the European honey buzzard, the common buzzard, and the lizard buzzard.

So, you may be wondering how new world vultures or turkey vultures came to be known as buzzards in North America. The blame can be placed upon British colonists and other settlers from Europe.

Are buzzards dangerous?

The term buzzard is used in different contexts and for different species all around the world.

In most parts of the United States, buzzard is used to refer to hawks. However, in other places in the US, it is used to refer to a vulture. Buzzards have a darkish-brown upper-body and pale under-body parts with reddish-brown streaks on their bellies. A pale band across the breast region can also be seen in buzzards. Their primary feathers are dark black with a trailing edge pattern and a short and broad grey-brown tail with narrow bars and a terminal band of dark color.

These birds of prey, unlike other birds, don’t look for tree branches to perch on or twigs and leaves to make their nests.

These seemingly intimidating birds of prey are actually not that aggressive or dangerous. Buzzards are a common, widespread bird-like vulture in the US, living in dry and mountainous regions. It would be rare for a buzzard to attack you; it will only attack if it gets distressed or concerned about you taking its eggs or coming near its nest. They usually don’t have any incentives to attack humans or their pets otherwise. They also lack in physical attributes that would make them a threat. Even though they are known to be carnivorous (sometimes omnivorous), they only eat dead animals and not living creatures except for snakes, small birds, and rats that fall under their prey-predator list.

What is the wingspan of a vulture?

Vultures are big birds with broad wings. A variety of wingspans can be seen in various species and subspecies of vultures.

The black vulture has a wingspan in the range of 4.5-5 ft (1.3 m-1.5 m). Griffon vultures have a span of 7.5-9.1 ft (2.3-2.8 m), giving them a little more length and width in their wings than the other vulture groups. The red-headed vulture, which is often mistaken as a buzzard, has a wingspan of about 6.5-8.5 ft (2-2.6 m).

Most of the birds lack a strong sense of smell. However, the mighty vultures are known for their incredible sense of smell. Buzzards use their sense of smell and keen eyes to locate food, known as carrion. Flying low down, they try to detect decaying dead animals.

Vultures have a remarkable ability to sniff out a dead body or critter from a faraway place. The unique sulfurous compounds of decaying matter make them easier to smell from above for vultures.

There are white-headed vultures (Trigonoceps occipitalis) seen in Africa. Due to habitat degradation, a large number of vultures with a white color on their head is declining. Also, cases of poisoning of carcasses are a reason for vulture deaths.

Who flies higher, vultures or buzzards?

It is common to mistake a vulture for a buzzard or vice versa when looking at them as they fly.

While in flight, a buzzard looks like it is gliding and soaring high above with its wings in the shape of the letter V. This is similar to turkey vultures. The scavenger bird is a large, broad bird with rounded wings, a short neck and a fanned and finely barred tail with dark wingtips.

As for vultures, they are often seen circling around in tight circles in the sky. The same can be said for eagles and hawks.

Vultures and buzzards, and other birds of prey are typically associated with feeding on carcass as meals during their scavenging hunts.

However, on rare occasions, turkey vultures catch and kill live animals. As per aircraft reports, the turkey vulture (often known as the buzzard) flies up to heights of 20,000 ft (6096 m). They can travel long distances like 200 mi (320 km) per day.

Talking about the highest-flying bird, this title goes to the Ruppell’s griffon vulture. This Endangered species keeps the ecosystems healthy, eating the carrion all around Africa.

Here at Kidadl, we have carefully created lots of interesting family-friendly facts for everyone to enjoy! If you liked our suggestions for buzzard vs vulture: differences between scavengers explained for kids! Then why not take a look at chameleon habitat: curious facts on this tree reptile explained! or chimpanzee skull: fascinating ape bone facts that kids

Disclaimer

At Kidadl we pride ourselves on offering families original ideas to make the most of time spent together at home or out and about, wherever you are in the world.

We try our very best, but cannot guarantee perfection. We will always aim to give you accurate information at the date of publication – however, information does change, so it’s important you do your own research, double-check and make the decision that is right for your family.

Kidadl provides inspiration to entertain and educate your children. We recognise that not all activities and ideas are appropriate and suitable for all children and families or in all circumstances. Our recommended activities are based on age but these are a guide. We recommend that these ideas are used as inspiration, that ideas are undertaken with appropriate adult supervision, and that each adult uses their own discretion and knowledge of their children to consider the safety and suitability.

Kidadl cannot accept liability for the execution of these ideas, and parental supervision is advised at all times, as safety is paramount.

Sponsorship & Advertising Policy

Kidadl is independent and to make our service free to you the reader we are supported by advertising.

We hope you love our recommendations for products and services! What we suggest is selected independently by the Kidadl team. If you purchase using the buy now button we may earn a small commission. This does not influence our choices. Please note: prices are correct and items are available at the time the article was published.

Kidadl has a number of affiliate partners that we work with including Amazon. Please note that Kidadl is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to amazon.

We also link to other websites, but are not responsible for their content.

Read our Sponsorship & Advertising Policy

Let’s clear the air: a Vulture is not a Buzzard

anniechateauneuf

#fontanalibexplores, Action/Adventure, Animals, Bald Eagles, birds, birdwatching, Black Vultures, Books, Buteo, Buzzards, Culture, Education, Environment, Genre, History, Hobbies, Kids, Migration, Nature, NC Live, NC-Cardinal, Nonfiction, ornithology, reading, Science, Teen, Turkey Vultures, Uncategorized, Western North CarolinaBirdclub, Birding, birds, Buteo, Buzzards, Cathartesaura, Committee, Coragypsatratus, Eagles, Environment, Evolution, Factchecking, Fontana Regional Library, Hawks, India, Kettle, Misnomers, Nature, NC, NCLIVE, Rabies, science, Settlers, Sylva, Urohidrosis, Vultures, Wake, WNC

Today’s blog focuses on the Turkey Vulture, another one of the most commonly seen birds here in the Southeast. Before we talk about identifying characteristics though, I thought we could dive into the semantics of the terms vulture and buzzard, because it can be pretty confusing.

Before researching this topic, whenever I heard the word “buzzard” I thought of the big birds that are known for eating carrion and foreboding doom. First lesson in semantics here: these flocks are called a committee, a kettle or (my favorite) a wake, and they’re usually circling above an unfortunate creature that strayed too close to the road.

However, the Latin word for buzzard is buteo, which is the genus (genus is the taxonomic category above species and below family) that hawks fall into. These birds that are hovering over a carcass in the road are actually vultures and have no reason to be called buzzards at all besides a mistake that was made centuries ago that somehow stuck.

So why do we think of vultures when we hear the word buzzard?

Well, before America was colonized, buzzard was used to describe any bird in the buteo genus, in other words, any raptor with broad wings, sharp beaks and deadly talons used for hunting small animals. The term vulture was used for birds with naked heads and necks that scavenge for their meals.

When America was being colonized, English speakers noticed that, as Jan Freeman wrote in an article I found (using NCLive) for the Boston Globe, “North America’s vultures, like England’s buzzards, make those lazy circles in the sky; close enough, no doubt, for settlers who, after all, had to call the trees and birds something while they got on with surviving.” (1)

So “close enough” is why we picture vultures when we hear the word “buzzard” which should actually bring to mind one of the many hawks that are classified under the genus “buteo”. Peterson’s guide to hawks has a similar viewpoint on the topic: “The misnomer “buzzard” was given to the […] vultures by early settlers, who thought these birds were related to the European buteo with this name. Unfortunately, the name is still in common use.” (2)

Now, among the vultures of the world; we have Old World Vultures and New World Vultures. Even though these birds are very similar they are not closely related. They are a result of convergent evolution, a process that, over time, causes two species to evolve and adapt similarly in two different environments.

Turkey Vulture. Photo by Peter K Burian – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

Certain differences between the two show us that they evolved from different ancestors. New World Vultures have weaker feet; like storks, these vultures have feet that are made for walking, as opposed to the stronger feet of the Old World Vultures that are made for catching live prey. Another difference between the two is the way New World Vultures use their sense of smell to find carrion and an Old World Vulture uses its sight. New World Vultures also have no voice box and, one more difference, perhaps the most intriguing of all; New World Vultures exhibit the (slightly disgusting, but also pretty cool) behavior of urohidrosis, the act of defecating on their legs as a way to cool down.

Even though this behavior might make you a little queasy, it’s actually very helpful to the environment. The acid in the vultures’ droppings is so strong, it kills any bacteria left on the ground that came from the carcasses that the vultures were feeding on. Vultures get a bad rap because they only eat dead things (they are known as obligate scavengers because their diet is limited almost exclusively to carrion), but the truth of the matter is that if we didn’t have vultures on clean up duty, we would have a serious problem dealing with the spread of bacteria from dead animals. For instance, India is experiencing a sharp rise in the spread of rabies because of a recent and devastating decline in vulture populations. The decline was caused by the 1993 introduction of a drug that farmers used to treat injured or ill livestock.

So now that we’ve learned to love these giant birds, we can move on to identification.

Of the three types of vultures that live in North America, the Turkey Vulture, the Black Vulture and the California Condor, there are only two that we see here in North Carolina; the Turkey Vulture and the Black Vulture. The Turkey Vulture is so named because of its resemblance to a turkey due to its red and naked head. The Black Vulture is completely black with just a patch of white on the underside of its wingtips.

Turkey Vulture. Notice the two toned coloring of the wings and how far the tail extends past the feet.

Turkey Vultures are bigger than Black Vultures, and they have a bright red head. In our area, when you see a big, huge bird soaring above you it is most likely a vulture, so look for identifying characteristics such as the flight pattern, and the size, color, and shape of the wings. A Turkey Vulture’s wings are split in half by dark patagial (shoulder) feathers and lighter trailing feathers. Its tail and wings will also be longer and more narrow than those of the Black Vultures.

Turkey Vulture VS Black Vulture

Now, we do have Bald Eagles in Western North Carolina, so in order to be sure you’re not seeing a Bald Eagle, it’s helpful to know that the Bald Eagle is much bigger than the Turkey Vulture. Bald Eagles also have “fingertips” similar to the vultures, but a Bald Eagle will not have as much of a bend in their shoulders. Also, a Bald Eagle will have a very smooth flight compared to the Turkey Vulture, who, when soaring, tends to teeter sharply back and forth on its wings. (7)

Bald Eagle. Photo by Ryan MacFarland

Happy birding! I hope this blog helps you identify between vultures and eagles, sometimes it’s pretty tricky but, like all things, the more you practice, the easier it will be. For some inspiration check out some books from our bird-watching collection. Follow this link to place a hold on All Things Reconsidered, a memoir by Roger Tory Peterson, one of the world’s most famous birders.

Sources:

- Freeman, J. (1998, Apr 26). Household words, buzzards at bay. Boston GlobeRetrieved from https://login.proxy066.nclive.org/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/405223000?accountid=10928

- p. 15 Peterson Field Guide to Hawks William S. Clark/ Brian K. Wheeler

-

Vultures great benefit to people, environment. (2017, Feb 23). Springfield News Leader Retrieved from https://login.proxy066.nclive.org/login?url=https://search.

proquest.com/docview/1870846764?accountid=10928

-

https://www.brighthub.com/science/genetics/articles/68007.aspx

- Campbell MO (2014) A Fascinating Example for Convergent Evolution: Endangered Vultures. J Biodivers Endanger Species 2:132. doi: 10.4172/2332-2543.1000132

- Biswaranjan P, Sushil Kumar D (2016) Diclofenac Induced Vulture Deaths in Odisha, India: Time to Debate or Conserve Them?. Pharm Anal Acta 7:507. doi:10.4172/2153-2435.1000507

- https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Turkey_Vulture/id

Rate this:

Like this:

Like Loading…

A Buzzard is NOT a Vulture

SouthernArizonaGuide.com

In the United States, when someone refers to a buzzard, they are, in reality, usually talking about a turkey vulture, a member of the New World vultures. Arizona has very few buzzards, and lots of turkey vultures.

Turkey Vulture In Flight

Elsewhere in the world, a buzzard is in the same family as Old World vultures; classified “accipitridae – in the Buteo genus.

In the United States generally and Arizona in particular:

Buzzards are Raptors (genus buteo), a kind of hawk. Buzzards hunt and kill prey. Of necessity, they have strong feet for grasping live prey. While their eyesight is excellent, their sense of smell is poor. In addition to live prey, buzzards will eat carrion.

Turkey Vultures (Arizona) do not (usually) hunt and kill prey. They have weak feet because they don’t use them for grasping live prey. They dine almost exclusively on carrion (aka dead animals). Turkey vultures have a keen sense of smell. In Arizona, they are often erroneously called a buzzard. Vulture classification includes condors.

Turkey Vulture

Black Vulture are regularly found only in Arizona. However, they are occasionally sighted in New Mexico and California.

Black Vulture at Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum

Black vultures are rare in Arizona.

Condors are vultures. With nearly 10-foot wingspans, California condors are the largest flying bird in North America. The Andean condors are even bigger. In prehistoric times, condors were numerous throughout the territory that would become the United States. They dined on big animal carcasses. “Big” meaning huge mammoths larger than African elephants, 6000 pound sloths; ancient (now extinct) bison twice the size of our American buffaloes. Mostly due to the activity of humans, by 1982, only 22 condors survived in North America, all in California.

Placed on the Endangered Species List in 1967, captive breeding programs have resulted in some success. In 2011, some 70 California condors were flying free over the Vermillion Cliffs of Central Arizona between Lake Powell and the Grand Canyon.

CLICK HERE for more information about condor captive breeding programs.

• Privacy

Search for:

Search by Category

Search by CategorySelect CategoryADA AccessibleAdventures Archaeology Biking Birding Boating-Fishing Camping & RV Parks Daytrips Educational Entertainment Ghost Towns Golf Guided Tours Gunfighting Hiking Pet Friendly Horseback Riding Kid’s Stuff NightLife Performing Arts Scenic Back Roads N RoadTrips Wine TastingAstronomyBooksCritters and PlantsCrossing the Border – New MexicoCuisine – Type American Cuisine Asian Burgers Eclectic Gluten Free Italian Mexican Pizza Pubs N Breweries Sandwiches Seafood Specialty Markets Steak Sunday BrunchDining – Restaurants Catalina Foothills Dining in Bisbee Dining Marana Dining-Central Dining-Downtown Dining-East Dining-North Dining-South Dining-Tubac Dining-West Fourth Avenue Southeastern Arizona DiningDining ReviewsEnvironmentEvents – FestivalsFree or Nearly soGalleries, Art, ArtistsGardeningGeographic Area Amado-Arivaca-Ruby Area Benson Area Bisbee Central Tucson Area Desert Museum Downtown Area Eastside Area Elsewhere Florence Area I-19 Corridor Marana Mt Lemmon Area New Mexico Northside Area Patagonia – Sonoita – Elgin Sabino Canyon Area Sierra Vista Area Sonoita-Elgin Southeastern Arizona Southwestern Arizona The Missions Tombstone Area Tubac Area Tubac-Tumacacori Tumacacori Area Westside Willcox Area YumaGhost ToursGhost TownsLocal History Apache History Downtown Local History – Bisbee Local History – Cochise County Local History – Tombstone Local History – Tubac Local History – Tucson Local History – Yuma Old West History Tohono O’odham History Wyatt EarpLodging Apache-country Bisbee Lodging – SouthEastern Arizona New Mexico Tombstone Lodging Tubac Lodging Tucson LodgingMuseumsOld WestParks & GardensSelf Guided ToursShopping Deals Farmers’ MarketsSouthern Arizona AttractionsSummerSweet Deals!ToursUncategorizedUseful TriviaVideoswidget_mapsWildlifeWineries Sonoita Elgin Wineries Willcox Wineries

. .

View the Extended Calendar

View the whole Calendar here All Events

Events

- SU

- MO

- TU

- WE

- TH

- FR

- SA

- 31

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 1

- 2

- 3

What is the difference between buzzards and vultures?

Buzzards and vultures may seem like common, familiar birds, but the two terms can be confusing and are often mistaken for completely different species.

What is a neck?

Vultures are generally considered to be hairless, long-necked scavengers that have a bad reputation for eating carrion. However, these birds actually provide a valuable ecological service as they clean up carcasses and help prevent the spread of disease to other wildlife, including humans. There are 23 species of vultures in the world in total – in two different groups. Seven species of New World vultures belong to Cathartidae is a family of birds, while 16 species of Old World vultures are in the family Accipitridae . Even though these species are only distantly related, they do share many traits and both groups are easily recognizable as vultures.

What is a buzzard?

instagram viewer

There are 26 species of birds in the world that bear the name buzzard, including the European buzzard, lizard buzzard, forest buzzard and long-legged buzzard.

Buzzards are a species of hawk, specifically the buteos. They are medium to large sized hawks with wide wings, ideal for soaring in heat currents. Most buzzards prefer relatively open areas where they can easily hover and search for prey. Unlike vultures, buzzards hunt for their food and prefer to catch live prey, although they will occasionally snack on a carcass, especially if other food sources are scarce.

While in Europe, Africa, Asia, Indonesia and Australia these birds are called buzzards, in much of the Americas hawks are called the same species of birds, buteo open country. The familiar red-tailed hawk, for example, if found in Europe, would most likely be called the red-tailed buzzard. Even the field guides have a rough-legged buzzard ( Buteo lagopus ) is called the rough-legged hawk in its North American range.

Vultures can be called buzzards

Vultures and buzzards get confused when the names of these birds overlap.

The early colonists called the large soaring birds they spotted in the skies of North America “buzzards” because they were similar to the flight pattern of buzzards in Europe. However, the birds actually seen by the colonists were not Buteo hawks, but turkey vultures and black vultures, which are widespread in eastern North America. The name stuck, and even today, North American vultures are still called buzzards, turkeys, or black buzzards.

Vulture turkey. Rus / Flickr / CC on 2.0

Buzzards against vultures – who is who?

Ultimately, whether the bird is a buzzard or a vulture depends on who you ask and where you ask them.

- Turkey vulture (commonly known common name)

- Turkey buzzard (common regional name or European variant for itinerant birders)

- TUVU (four digit abbreviated bird code)

- TV (simpler name code)

- Vulture or buzzard (single mention if there are no similar species in the region)

- Cathartes Aura (scientific name, internationally recognized)

This naming confusion is why it is important for ornithologists to learn the scientific names of birds, especially when they are birdwatching in different parts of the world.

Understanding the differences between buzzards and vultures, including how different words can refer to the same birds, can help birders better communicate which birds they see and share their observations with others.

Difference between vultures and buzzards (birds)

Understanding the key differences between vultures and buzzards is important. These two birds have been confusing many people for a long time, but there are some fundamental aspects that distinguish the two birds. The vulture is a scavenger and there are two types of vultures. There are new world vultures and these include the Andean condors. There are also Old World vultures, and these are the ones that are seen cleaning up on the carcasses of animals that have died.

The buzzard, on the other hand, is a unique bird of prey. It is mostly found in Europe but is spreading to parts of Asia. To better understand birds, this article shows their unique traits and the differences between them.

What kind of vultures?

As you can see above, vultures kill birds of prey. Interestingly, they are found on all continents except Australia and Antarctica. One of the popular traits of these birds is that they have a bald head that lacks the usual feathers. For a long time, this feature has been attributed to helping birds keep their heads clean when feeding.

In addition, bare skin helps in thermoregulation. There are new world vultures and they are found in areas with warm temperatures. There are also Old World vultures, but they are not closely related. Vultures rarely attack healthy animals. They mainly attack sick or dead animals. Following are some of the characteristics of these scavengers.

- They are bald

- They have wide wings to glide

- They have far vision

- They have prominent eyebrows and long eyelashes.

- Most vultures prefer the bones of their carcasses to the flesh.

What are buzzards?

These are birds of prey that live in a wide variety of habitats. They can survive almost anywhere. They can live in grasslands, forests and even deserts. These birds mainly feed on the remains of dead animals or small mammals. Like vultures, they can fly high, and their wings have been found to help them adjust to the ever-changing air currents.

Facts about buzzards:

- There are not enough of them

- Couples mat for life.

- They do not form herds. However, they can be seen together during the migration.

- They mainly feed on rabbits, but they may also feed on small mammals and carcasses.

- Females tend to weigh more than males, which is why males are considered ideal hunters.

Differences between vultures and buzzards

1. Physical differences between vultures and buzzards

Vultures have weak legs, which is normal for them because they do not use them to grab their prey.

Buzzards do not have bald heads, but vultures are known for their bald heads.

Buzzards have strong beaks and claws to kill and feed on their prey. Vultures, on the other hand, rarely kill their prey. Therefore, their beaks are rather weak.

2. Senses of vultures and buzzards

Vultures generally have a very keen sense of smell. They can smell carcasses from miles away. As for buzzards, they have a poor sense of smell.

3. Habitat differences

Buzzards can live in almost all environments. They can live in mountains, lowlands and deserts among other places. Vultures, on the other hand, barely live in cold regions. They thrive in Africa, the drier parts of Asia, and warm areas in Europe.

4. Diet Differences

The main diet of vultures consists of dead animals. The only type of vulture that prefers a different diet is Gyphohierax angolensis, which feeds on palm oil fruits.

5. Behavior

The behavior of the two birds is different in that although buzzards are predators, vultures are scavengers.

Buzzards tend to migrate. Vultures do not migrate.

Vultures have good eating habits. They will be careful while eating. As for the buzzards, they will dig into food and get dirty while eating. The buzzard is smaller. Therefore, they move quite quickly in the air because they are lighter.

Vultures vs. Buzzards

Brief information about vultures and buzzards

- Both vultures and buzzards are birds of prey and can sometimes be confused with each other.

- However, a lot of research has been done on them over the years, and it has become easier to distinguish between the two birds.

- Vultures are popular for their bald heads and long necks.

- Buzzards, on the other hand, do not have such necks and bald heads.

- Both birds have distinctive features to help them survive.

- For example, vultures rarely kill their prey.

- Therefore, they have weak legs and beaks, because they do not need features, since they will not kill their prey.

- Buzzards, on the other hand, are killers. They have strong beaks to plunge into their prey.

- The legs of the buzzard also have considerable strength because they need them to grab their prey.

- So from this article we can conclude that both birds are similar in some ways, but they also have their differences mainly in terms of survival and habitat. Part 20. Eagle, vulture, vultures, bearded vulture, eagles, buzzards

White-tailed eagle ( Haliaeetus albicilla )

Eagle – the word, apparently, is a bookish one. In the vernacular, eagles hardly differ from eagles. Whitetail, as the name of this bird, is first found in the 18th century. The epithet “white-tailed”, “white-tailed” is attached to this bird in other European languages.

The word “eagle”, mentioned in Russian sources of the 17th century, apparently refers to small species of eagles (spotted eagles).

Inhabits the coasts of rivers, lakes, seas, mainly where there are tall trees suitable for nesting, or rocks.

Ordinary vulture ( Neophron Percnopterus )

lives in desert and half -desert areas near the mountains or cliffs, hills, etc. )

The origin of the word “sip” is not clear, but in any case it has been used since the 18th century.

Habitat: dry open landscapes in both mountains and plains; vultures need rocks and cliffs for nesting.

Black vulture ( Aegypius monachus )

The name “vulture” (Latin gryphus from Greek γρύϕ) among ancient peoples refers to a bird with a hooked beak, eagle wings and wings. In the modern sense, it was first applied to this bird by French academics in 1666, passed from them to Buffon, and from him to later authors.

In Russian, the word vulture, as the name of a legendary animal, has been found for a very long time; the vulture as a heraldic emblem has been known to us at least since the 16th century, and possibly even earlier. The black vulture is a book name, although the bird is not actually black, but grayish-brown (only young birds in the first annual plumage are blackish). However, in flight against a light background of the sky, the vulture appears black.

Inhabits mainly mountains, but sometimes also occurs on plains. It is possible that birds nest on the plains when especially favorable feeding conditions occur – the presence of a large amount of carrion.

Bearded vulture , or lamb ( Gypaetus barbatus )

“Lamb” – translation of the Western European name of this bird Lammergeyer, but the meaning of this name is incorrect, since the meaning of this name is a scavenger. The name “bearded man” – from a bunch of stiff feathers or bristles under the beak, forming a beard; in Russian, both names are bookish.

Settles in open rocky areas of mountains located above the tree line. Golden Eagle Scottish Erne). The name of the Russian writers of the 18th century, in particular, V. Levshin, “stone” and “golden” eagle – probably a translation from German (Steinadler, Goldadler). The name “Kama eagle”, according to the same author, is explained by the fact that the Bashkirs caught golden eagles and took them out of their nests on the Kama for sale in the Kyrgyz steppe. From 19centuries, many Russian scientists took two specific names for eagles: golden eagle and khalzan; at the same time, young birds were called golden eagle, and old birds were called halzan. The name golden eagle (burkut, burkut) is Turkic, and is widespread among the peoples of Central Asia. It is curious that the inhabitants of Wales for large birds of prey have the name bargud (“bargud”), the similarity of which with the word “eagle” deserves attention.

Habitat: in the southern part of the distribution area – with rare exceptions – mountainous areas; in Eastern Europe and Siberia – on the plains, in tall forests and in the mountains.

The combination of nesting and feeding conditions necessary for the golden eagle is reduced to the presence of rocks or trees where it nests, and sufficiently wide open spaces, since the wingspan makes it difficult for it to hunt between trees in the forest. Therefore, in the taiga, the golden eagle is found in those places where forests are interspersed with open places – river valleys, swamps, etc. The golden eagle avoids populated areas.

Imperial Eagle ( Aquila heliaca )

The name “imperial eagle” comes from the fact that this bird is usually found in the steppes on barrows and grave mounds. The Asian peoples have the name “karakush”, that is, “black bird” – in contrast to the golden eagle.

The cemetery prefers mixed and deciduous forests, sometimes found in pine forests, in the forest-steppe and steppe zone it inhabits areas overgrown with woody vegetation.

Hawk , or Long-tailed , Eagle ( Aquila fasciata )

Booted Eagle ( Aquila pennata )

Inhabits mixed, but more often deciduous, tall forests, both on plains and in mountains.

Common buzzard , or buzzard ( Buteo buteo )

The words “buzzard” and “buzzard” seem to be synonymous in the folk language. The etymology of the first is not clear, perhaps it comes from the Turkic word “sary” – “yellow” (due to the color of the bird). On the other hand, in Polish this bird is called “sarn”, so the word “buzzard” may also have a Slavic origin. Buzzard – from moaning, plaintively screaming, begging, associated with the plaintive cry of a bird. It is interesting that the bird has a similar name in Germanic languages - buzzard, Bussard (from the old German Bus-aro, which means “meowing eagle”).

Settles in wooded areas covered with coniferous, mixed or deciduous forests, on plains and in mountains. On migration it also occurs in open landscape.

Rough-legged buzzard , or Rough-legged buzzard ( Buteo lagopus )

Rough-legged buzzard is a book name common in meaning to almost all European languages.

In the north, the local name for this bird is the mousetrap, or mouser. It is called a zimnyak in places in the middle lane, where it appears in the cold season.

In nesting time lives on open landscapes – in tundra and forest-tundra, on wintering – in steppe and cultivated landscape, in forest zone – in river valleys, avoids continuous forests.

Steppe Buzzard , Long-legged Buzzard ( Buteo rufinus )

Habitat: open dry landscape – deserts, steppes and semi-deserts

European or common , Honey buzzard ( Pernis apivorus )

Inhabits tall forests, usually mixed or deciduous, rarely – in the north – coniferous (pine forests). The distribution is associated with the presence of Hymenoptera (wasps), so the combination of forest with open spaces is preferred.

Ordinary snakes , or Krachun ( Circaetus Gallicus or Circaetus Ferox )

The name “Snakes” comes from the nutrition of this bird, the food of which serve, mainly, reptiles and earthquakes.

The origin of another name for this bird – krachun – is unclear.

In the north of the distribution area it settles in forests, in the south – in dry areas with fairly developed, but at least rare woody vegetation. Prefers plains, avoids mountains.

The Vultures read online by Wilbur Smith (Page 18)

The Buzzard was proud of his ancestors, but knew that they had achieved wealth and title by skillfully avoiding the gallows and the acquaintance of the executioner. In the last century, all maritime states have united to destroy corsairs and pirates, a plague that has hindered maritime trade since the time of the pharaohs.

No, you can’t get away with this, boy, he thought, shaking his head regretfully and holding the news page up to the eyes of the sailors, none of whom could read.

– It’s a pity, but the war is over. We’ll have to release these gentlemen.

— Captain, does this mean that we are losing our prize money? the helmsman asked plaintively.

– Yes, if you don’t want to be hanged for piracy in Greenwich.

He turned to Colonel Schroeder and bowed to him.

— Sir, it looks like I owe you an apology. He smiled charmingly. “I was sincerely mistaken, and I hope you will forgive me. I haven’t received any news from the outside world for several months now.

The Colonel stiffly answered his bow, and Cambrai continued:

— I am pleased to return your saber to you. You fought like a real warrior and a true gentleman. The Colonel bowed a little more kindly. “I will give the order to release your crew immediately. You can of course return to Table Bay and continue sailing from there. Where are you going, sir? he asked politely.

– If not for your intervention, we would have sailed to Amsterdam. I am bringing to the Company Council a ransom demand for the newly appointed Governor of the Cape of Good Hope, who, along with his angel wife, has been captured by another English pirate, or rather, he amended, another English privateer.

Cambrai looked at him.

— Is your governor’s name Petrus Van de Velde and did he sail aboard the Standvastigade? – he asked. “Did the Englishman Sir Francis Courtenay capture you?”

Colonel Schroeder was surprised.

— Indeed, sir. But how do you know this?

— I will answer this question in due time, Colonel, but first I must learn something. Are you sure that Standvastigade was captured after the two powers signed a peace?

– My lord, I was a passenger aboard the Standvastigade when the ship was hijacked. Of course, I’m sure it was an illegal takeover.

Last question, Colonel. Would it not greatly enhance your reputation and professional standing if you were able to free Governor Van de Velde and his wife by force of arms and return the valuable cargo from Standvastigeide to the West India Company?

Such a wonderful suggestion left the Colonel speechless. Violet eyes and sunshine-like hair, which he had never forgotten since the last time he saw them, returned in great detail.

The promise of those sweet scarlet lips meant to him even more than all the treasures, spices and gold bars. How grateful Katinka would be to him for her release, how grateful her father, the President of the Company’s governing Council, would be. Perhaps this is the greatest success that fell to him in his life.

He was so excited that he could hardly force himself to nod his head in response to Buzzard’s question.

“Then, sir, I think we should discuss a position to our mutual advantage,” Buzzard said with a winning smile.

The next morning the Seagull and the Swallow returned to Table Bay, and as soon as they dropped anchor under the cover of the ship’s guns, the Colonel and Cambrai went ashore. A detachment of slaves and prisoners, having entered the water up to their shoulders, dragged their boat to the shore before the wave could turn it over, and they set foot on land without getting their shoes wet. Walking side by side to the fortress, they were a striking, unusual couple.

Schroeder was in uniform, in full dress, with scarves and ribbons; the southeast wind fluttered the feathers on his hat. Cambrai was gorgeous in his red, red, yellow and black plaid. The population of a distant village had never seen a man dressed like that and poured out into the streets to stare.

The attention of Cambrai was attracted by beautiful young Javanese slaves, resembling dolls: he spent many months at sea without a woman’s caress. The girls’ skin shone like polished ivory, and they had dark deep eyes. Many were dressed European-style in fashionable dresses donated by their owners, small neat breasts poking out under the lace of their bodices.

Cambrai received rapturous attention like a marching monarch, raising his ribboned hat to the youngest and most beautiful girls; at his frank glance and furiously tousled mustaches, they answered with chuckles and blushed.

The guards at the castle gate greeted Schroeder, who was well known to them, and the two entered the fortress unhindered.

Cambrai carefully examined the fortress, assessing the strength of its resistance. Let there be peace now, but who can say what will happen in a few years? Someday he might have to lay siege to those walls.

He saw that the fortress walls were built in the form of a five-pointed star. The model for them was clearly the new fortress of Amsterdam, the first to adopt such an innovative arrangement of defensive fortifications.

Each of the five ends of the rays was crowned with a redoubt, the protruding walls of which allowed the defenders to keep the foot of the fortress walls under fire; earlier this space fell into a dead zone and became defenseless. Once the massive stone walls are completed, the fortress will be virtually impregnable against anything but a very long siege. Digging under the walls and blowing them up can take many months.

However, the work is far from complete. Hundreds of slaves and prisoners labored in the moat and on the unfinished walls. Many cannons were still lying in the yard; they have not yet been installed in the redoubts overlooking the bay.

“What an opportunity missed,” Buzzard mourned to himself. This information came to him too late. “With the help of a few Knights of the Order, with the help of Richard Lester and even Franky before our quarrel, we could have captured the fortress and sacked the city. If we had joined forces, the three of us would have the entire south Atlantic from here and could intercept any Dutch galleon trying to round the cape.

After examining the fortress, he noticed that part of it was being used as a prison. From the dungeon, located under the northern wall, a procession of prisoners and slaves in leg irons was led. Above the dungeon, as on a foundation, they built barracks for the garrison.

The whole yard was occupied with stone and scaffolding, and a detachment of musketeers was practicing in the only free area, in front of the arsenal.

Ox-drawn wagons loaded with logs and stone drove in and out of the gate or stood in the yard, and at the south wing of the building a superb carriage waited in splendid solitude.

The horses, matched in color – gray, were so cleaned that their skin shone in the sun. The coachman and footman are in the green and gold livery of the Company.

— His Excellency came early to his office today. We don’t usually see him until noon,” Schroeder remarked. “The news of your arrival must have reached his residence.

They climbed the south wing stairs and entered through teak doors carved with a Company cross. In an anteroom with a polished yellowwood floor, the adjutant took their hats and led them into the anteroom.

“I’ll report to His Excellency about you,” he said and backed out. He returned in a minute. “His Excellency is waiting for you.

The narrow windows of the audience chamber overlooked the bay. The hall was furnished with a strange mixture of heavy Dutch furniture and Oriental things. A bright Chinese carpet covered the polished floor, and a collection of fine Ming-style lacquered ceramics stood in glass-fronted cabinets.

Governor Kleinhans turned out to be a tall, thin, middle-aged man; his skin was yellow from life in the tropics, and his face was wrinkled from official duties.

He was very thin, and his Adam’s apple protruded so much that it gave the impression of deformity; the fashionable wig on the head of the governor did not fit with the wrinkled face.

– Colonel Schroeder. He greeted the officer discreetly, his eyes fixed on the Buzzard with faded eyes in bags of drooping skin. – In the morning, without seeing your ship, I thought that you sailed without my permission.

– Excuse me, sir. I will give you a full explanation, but first let me introduce you to the Earl of Cambrai, an English nobleman.

“Scottish, not English,” Buzzard corrected.

Governor Kleinhans was impressed by the title; he immediately switched to perfect correct English, only slightly suffering from guttural pronunciation.

– Welcome to the Cape of Good Hope, my lord. Please sit down. May I suggest refreshing? Madeira glass?

Holding long-stemmed glasses full of amber wine, they sat in a circle on high-backed chairs, and the colonel leaned towards Kleinhans and said:

— Sir, what I want to tell you is a secret matter.

He looked at the servants and adjutant. The Governor clapped his hands, and they all vanished like a puff of smoke. Interested, he tilted his head towards Schroeder.

— Well, Colonel, what secret do you want to tell me?

Schroeder spoke, and the governor’s face lit up with greed and anticipation, but when the colonel made his proposal, the governor tried to show reluctance and skepticism.

– How do you know that this pirate, Courtney, is still where you last saw him? he asked Cambrai.

– Twelve days ago, the stolen galleon “Standvastigade” lay on land – on board, with the mast removed and the cargo transferred to the shore. I am a sailor and I can assure you that Courtney will not be able to go to sea until thirty days later. That means we have two more weeks to prepare and attack him,” Buzzard explained.

Kleinhans nodded.

— So where is this villain’s hiding place?

The Governor tried to ask this question casually, but his feverish yellow eyes gleamed.

“I can only assure you that his camp is well covered,” Buzzard answered evasively, with a dry smile. “Your people won’t find him without my help.

– Understood. With a bony finger, the governor dug into his nose and examined the piece of dry mucus that had been extracted from there. Without raising his head, he continued casually, “Naturally, you will not demand a reward for this help; after all, it is your moral duty to destroy the pirate’s nest.

“I will only ask for a modest refund for my time and expenses,” Cambrai agreed.

“One hundredth of the cargo we can return,” suggested Kleinhans.

“Well, not so modest,” said Cambrai. I half agree.

– Half! The governor straightened up, and his face became the color of old parchment. “Of course you are joking, sir.

“I assure you, sir, when it comes to money, I rarely joke,” Buzzard said. “Have you thought about how grateful the CEO of your Company will be when you return his daughter unharmed to him without paying a ransom?” This alone will greatly increase your pension, not even taking into account the cost of spices and ingots.

Thinking, the governor began to excavate in the second nostril and remained silent.

And Cambrai continued to exhort:

– Of course, as soon as Van de Velde is freed from the clutches of the scoundrel and arrives here, you will be able to transfer your duties to him and return home to Holland, where you will be rewarded for your long faithful service.

Colonel Schroeder told him how eagerly, having served the Company for thirty years, the governor was waiting for his resignation.

Kleinhans was excited by such a magnificent prospect, but his voice sounded sharp:

– A tenth of the returned cargo, but no share in the sale of captured pirates to the slave market. A tenth, and this is my final offer.

Cambrai depicted a tragic face.

— I will have to share the reward with the crew. Less than a quarter, I can’t agree.

“A fifth,” croaked Kleinhans.

“I agree,” said Cambrai, quite satisfied. “And, of course, I will need the help of an excellent military frigate that is stationed in the bay, and three squadrons of your musketeers under the command of Colonel Schroeder.

Also, my ship needs replenishment of gunpowder and shells, not to mention water and provisions.

An incredible effort was required from Colonel Schroeder, but by the middle of the next day, three detachments of infantry, 90 men each, lined up in the courtyard of the fortress, ready to board the ships. The officers and non-commissioned officers were all Dutch, but the Musketeers were a mixture of native troops: Malaysians, Hottentots recruited from the Cape tribes, Singhalese and Tamils from the Company’s holdings in Ceylon. They were all bent under the weight of weapons and shoulder packs, but they were all barefoot.

Cambrai, watching them pass through the gates in their flat black caps, green coats and white criss-cross baldrics, holding their muskets by the muzzle, remarked gloomily:

— I hope they fight as beautifully as they march, but I think they are waiting for surprise when they run into Franky’s sea rats.

He himself was able to take on board the “Seagull” only one detachment with luggage.

But even so, it will be crowded and uncomfortable on deck, especially if bad weather overtakes them on the way.

The remaining two detachments of infantry set off on a military frigate. An easier passage awaits them, because the De Sonnevogel – the Sun Bird – is a fast and comfortable ship. The Dutch Admiral de Ruyter captured this ship of Cromwell’s fleet during the battle of Kentish Knock, then the ship participated in de Ruyter’s raid on the Thames and only a few months ago came to the cape. A beautiful slender ship with a black hull and snow-white sails. It was noticeable that before sailing from Holland, the sails were changed on the ship, and all her gear and yards sparkled with newness. The crew consisted mainly of veterans who had gone through the last two wars with England, hardened and stern warriors.

So the captain of the ship, Captain Riker, was a seasoned, strong, experienced sailor, broad-shouldered and massive. He made no secret of his displeasure at finding that he would have to take orders from a man who had only recently been an enemy outside of the regular fleet, and who could be considered a true pirate.

He treated Cambrai coldly and hostilely, barely hiding his contempt.

A council of war was held on board the De Sonnevogel, and it did not go smoothly: Cambrai refused to name the destination, and Riker objected to any proposal by the Englishman. And only the intervention of Colonel Schroeder saved the expedition from collapse even before it left Table Bay.

With great relief, the Buzzard watched as the frigate weighed anchor and, with almost two hundred musketeers lined up along the rails and waving to the crowd of loudly dressed or half-naked women on the shore, followed the little “Seagull” towards the exit from the bay.

The deck of the Chaika itself was also packed with infantrymen, who waved their hands, chatted and showed each other landmarks on the mountain and on the shore, interfering with the sailors who were taking the Chaika away from the shore.

As the ship passed the point below Lion’s Head and felt the powerful pull of the South Atlantic, the noisy passengers fell silent, and as she turned and moved across the ocean, the first musketeer rushed to the rail and sent a long stream of yellow vomit straight into the wind.

The wind blew it all back into his pale face, splattering the bile-mixed remnants of the last meal all over his jacket, and the sailors laughed.

Within an hour, most of the soldiers followed the example of the first, and these offerings to Neptune made the deck so slippery and dangerous that Buzzard ordered to stand at the pumps and pour water over both decks and passengers.

“We have some interesting days ahead of us,” he told Colonel Schroeder. “I hope these beauties will have enough strength to come ashore when we reach our goal.

Even before the middle of the journey, it became obvious that his words were not a joke, but a cruel reality. Most of the infantrymen suffered from seasickness and lay like corpses on deck, their stomachs were empty. Captain Riker’s signal indicated that the situation on his ship was no better.

– If we send these people into battle straight from the deck, Franky’s guys will swallow them and not even spit out the bones. We’ll have to change the plan, said the Buzzard to Schroeder, who sent a signal to the Sonnevogel.

The ships lay adrift, and Captain Riker, with obvious displeasure, appeared on the boat to discuss the plan presented by the Buzzard.

Cambrai drew a schematic map of the lagoon and coastline on either side of the entrance to the strait. Three officers were examining her in the tiny cabin aboard the Seagull. Riker’s mood improved: he finally recognized the destination, he had the prospect of action and prize money before him, and finally Cambrai treated him to a good whisky. He agreed with the plan proposed by Buzzard.

— Here, about eight miles west of the entrance to the lagoon, there is another rise. The buzzard showed on the map. “Here the sea is protected from the wind, and it will be possible to land Schroeder and his musketeers on boats. From here they will walk. He jabbed at the map with a finger with spiky red hair. “The overland crossing and physical exertion will help his people get rid of seasickness. When they get to Courtney’s lair, their fighting spirit will revive.

– Do pirates have protection for entering the strait? Riker asked.

– They have batteries here and here, they cover the strait. The buzzard drew crosses on either side of the strait. “They are well protected and practically invulnerable to fire from ships entering or leaving the bay.

He paused, remembering what kind of send-off these batteries had arranged for the Seagull when she was leaving the lagoon after an unsuccessful attack on the camp.

Riker sobered up at the thought of exposing his ship to coastal gunfire.

“I can capture the battery in the west,” Schroeder promised. “I’ll send a small force to the cliff. They do not expect attacks from the rear. But I will not be able to cross the channel and do the same with the eastern battery.

“I’ll send my squad to these cannons,” Riker said. – It is only necessary to develop a system of signals in order to coordinate actions in the attack.

For another hour they worked out flags and smoke signals to carry messages from ship to ship and to shore.

By this time, Riker and Schroeder’s blood was boiling, and they were vying with each other for the opportunity to gain military glory.

“Why would I risk my people when these heroes are willing to do the work for me?” Buzzard thought contentedly. And said out loud:

Congratulations, gentlemen. The plan is excellent. I suggest you postpone your attack on the coastal batteries until Colonel Schroeder has brought the main body of infantry through the woods and is able to attack the pirate camp from the rear.

“Quite right,” Schroeder readily confirmed. “But once the batteries on the cliffs are out of action, your ship will distract the pirates by entering the lagoon and bombarding their position. For me, this will be the signal to attack the camp from the rear.

– We will support you with all our strength, – nodded pleased Cambrai, thinking: “How he strives for glory!”

He resisted the urge to pat Schroeder patronizingly on the shoulder. “This fool will get his share of my cores as soon as I claim the prize.